What does the Green New Deal Mean for Justice & Farming?

The Green New Deal is increasingly becoming a hot topic in discussions about climate change.

Introduced by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Edward J. Markey earlier this year, the Green New Deal is a plan to fight climate change through moving away from fossil fuels, reducing greenhouse gas emissions across all sectors of the economy, and creating new jobs in the renewable energy sector.

The idea for the Green New Deal emerged from President Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, which sought to regulate the free market, manage the economy, and invest in farmland restoration, the arts, and job creation to put an end to the Great Depression.

With the Green New Deal at the forefront of the country’s political agenda, states and local communities are beginning to conceive of what a Green New Deal looks like for them.

But what does that look like for farmers, and what does it look like for farmers in Tompkins County more specifically? And, how can the Green New Deal work to center — not just work alongside — the voices and needs of those on the margins?

Trends in Farming Nationwide

1. America is losing farmland and family-scale farmers

The average size of farms are getting bigger, but the average net income of farms — even mid-size ones — has gone down. Four percent of U.S. farms are currently responsible for more than ⅔ of all agricultural production.

2. The farmer’s share of the food dollar is shrinking

Big brands are buying up smaller companies, and corporate consolidation has led to fewer choices in produce buyers and less market power.

3. Farmers are making most of their money from off-farm sources

In order to support themselves, farmers are increasingly having to turn to off-farm sources of income. Many farmers have off-farm jobs on top of working as farmers in order to stay on their land and keep their farm livelihoods.

5. There is a pervasive race and gender wage gap in the food chain

In the production, processing, distribution, and service of food, white men make the most money. A 2011 study found that the average hourly wage for a worker in the food production sector was $12.05 for white workers and $8.79 for workers of color.

Black and Latina women working in the food system make only half of every dollar that a white man makes. Men of color make slightly more than that, and overall, men make more than women.

What does this Mean for Local Farmers?

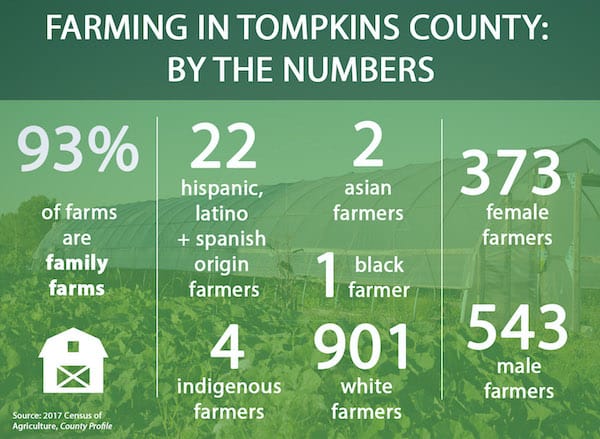

In the 2017 Census of Agriculture, there was just one black farmer, and 4 indigenous farmers in Tompkins County recognized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In New York State, there are only 139 black farmers out of 57,865 of farmers in the state.

Since the arrival of colonization, indigenous people have been products of genocide through violent displacement from their lands. White settlers resettled the land through slavery — which has become systemic exploitative labor practices — using Africans stolen and displaced from their homelands. These two factors combined to become the foundation for today’s capitalistic economy, which conventional agriculture can attribute its success to.

This systematic oppression can also be attributed to how farmers — referred to as producers — are defined by the USDA, which connects land access and business management to being a farmer.

Rafael Aponte grew up in the South Bronx and said he views food through a lens of justice. Rafael is currently the only black farmer officially recognized by the USDA in Tompkins County. He said he is considered a first-generation farmer despite the fact that the United States was founded on genocide and slavery.

“It’s very important not to erase what the contributions are of people of color in the United States,” Rafael said. “I’m also considered a first-generation farmer, which seemed very odd considering my ancestors were brought here to this country in order for agriculture hundreds of years ago. But the USDA considers me a first-generation farmer. So, we need to acknowledge those histories.”

How did we get here?

Although all small farmers are losing land to corporations, black farmers have disproportionately lost 90% of their historically owned land — which was unceded Indigenous land — since the start of the 21st century.

By the beginning of the 20th century, black farmers owned 15 million acres of land. The land was amassed in the 45 years following the civil war, and most of it was in the South.

For black families, owning land contributed to long-term stability and opportunities for economic advancement. While some land loss can be attributed to the Great Migration, our legislative system — grounded in systemic racism — stripped black farmers of their land through a variety of discriminatory practices, including partition sales, torrens acts, and tax sales.

Since the beginning of colonialism, the indigenous peoples of Turtle Island lost most of their land to white settlers and were subject to forced relocation and removal, massacres, discriminatory policies, and deceiving “treaties” which led to massive land loss.

However, this history isn’t just a part of the past and still greatly affects the lives of people of color today and indigenous people.

For example, the descendants of former enslaved people who purchased land often did not have a clear title to the land, and it became known as “heirs’ property.” Most common in low-income communities, this land is often bought by real estate companies and other parties against the will of owners, primarily people of color.

Through land loss and displacement to reservations, the forced assimilation of indigenous people into western culture led to loss in the biogenetic diversity of native foods and seeds, along with culture, language and knowledge. Currently, many indigenous nations are devoting resources to cultural revitalization and a strong force behind the food sovereignty movement. In Seneca Falls, the Gayogohono have a Culture and Language Revitalization Project to bring back the language and seeds to their land.

What does this mean for Ithaca’s Green New Deal Resolution?

On June 5, 2019, the City of Ithaca Common Council adopted a localized Green New Deal.

A part of the deal pledged to share the benefits of the plan’s sustainable goals, in order to “reduce historical social and economic inequities.”

Kirby Edmonds, Managing Partner for Training for Change Associates, said that looking at these inequities as a part of history undermines how pervasive they are today.

“They’re not historical, they’re persistent,” he said. “They’re current.”

Instead, he said, the Green New Deal presents an opportunity to face the problem head on instead of mitigate it within our current framework.

“There’s this one sentence that talks about historical inequities when for me the Ithaca Green New Deal, is about putting that problem in front of us and saying let’s get it done this time because if we don’t get it done this time, there won’t be a next time,” he said.

This marked shift in approach to the Green New Deal is not just about collaborating with groups on the margins, Rafael said, but about creating policy based on their directives.

According to Rafael, this could include a number of policy alternatives, including allocating personhood to Cayuga Lake, restoring hunting and fishing rights to indigenous groups, and establishing cooperatives to give communities control over their own food systems. These solutions must be rooted in food security, food access, and food sovereignty. Local models for policy and organizing can also be scaled up and implemented on much broader levels.

“The Green New Deal must incorporate all the different sectors of society that we wish to make a remedy on, and the Green New Deal is just that. A deal,” he said. “It’s a compromise. It’s a plan to put into place. We need a green revolution … We need a grassroots movement that will incorporate elements of justice into farming and food.”

–

Interested in hearing more conversation about how the Green New Deal could impact farmers in our community?

Check out a recording of our conversation, “Farming for Justice: How Green is the Green New Deal?” that took place October 8th via Zoom and at the Just Be Cause Center.

We would like to thank the following individuals and groups who served as panelists:

- Sunrise Movement Ithaca

- Elizabeth Henderson (Peacework Farm, NOFA Interstate Council)

- Rafael Aponte (Rocky Acres Community Farm, Youth Farm Project)

- Kirby Edmonds (Building Bridges)

To learn more about the Ithaca Green New Deal Resolution, visit the website.